Pat was one of hundreds of thousands of Americans who dodged the draft in the late 60’s but one of the very few who were imprisoned for it. It is now known that, during the Vietnam era, approximately 570,000 young men were classified as draft offenders, and approximately 210,000 were formally accused of draft violations. However, only 8,750 were convicted and 3,250 were jailed. Less than 0.5 percent were jailed.

The FBI persecuted Pat because of his activism at SF State. Pat was not just punished for evading the draft but also for his politics, his social class, and race. Due to the family’s financial situation, Pat could not afford a high-priced lawyer to get his federal charges dropped. Despite his mother’s political connections in the City of San Francisco and State of California, the federal government was not going to be deterred in making a statement about incarcerating one of SF State’s student strike leaders.

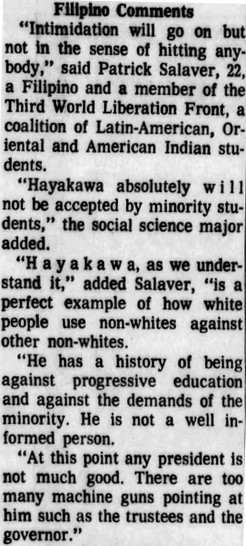

Of all the PACE student leaders, Pat is the only one identified by name as a TWLF Leader in a government report. The government used Pat’s quote from a widely distributed November 27, 1968, press report that criticized S.I. Hayakawa’s installation as President of SF State to identify him as a student leader. This press report was picked up by several major newspapers on the west coast.

While several students have been identified as PACE founders, Pat is the sole founder of PACE. All other students were charter members who he recruited personally by word of mouth and invited them to cultural, social and organizing meetings. In addition, both Dan Gonzales and Bob Ilumin identified that within the PACE organizational structure Pat was the Head Coordinator and all other leaders were Coordinators. The Third World student organizations did not follow the President, VP, Secretary and Treasurer organization used in western institutions. In Fall 1969, Pat quit SF State due to lack of financial support and the need to provide for the family. Pat got a job as a taxicab driver and other part-time work. The hardship the family experienced was not enough for Pat to avoid the draft as it had for others who were arrested for the same offense.

Pat did not report on November 25, 1969, to the Oakland Induction Center, scene of many war protests. PACE had been advising several Filipino males on avoiding the draft by encouraging them to attend college, but now Pat was unable to do the same. The FBI ordered Pat’s arrest July 1970; Pat was charged with refusal to report for induction and pled not guilty. In July 1971 Pat was found guilty by court trial and in September 1971, sentenced to a two-year term. He started serving his sentence at Safford Federal Correctional Institution in October 1971. The prison was in southeast Arizona, isolating him almost 1,000 miles away from his Bay Area family and friends. After serving a year in prison, Pat was paroled in October 1972 and received a pardon three years later as part of President Ford’s Clemency program.

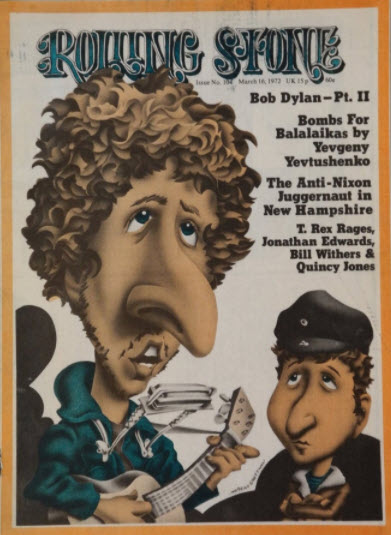

Rolling Stone magazine published an article called “Letters from American Political Prisoners” on March 16, 1972, by Timothy Ferris, an editor of the magazine who was not much older than Pat. In the portion of Pat’s letter that was published, he wrote, “By birth I am Filipino, a native of Southeast Asia and all too aware of the imperialistic and racist nature of the war. I am also aware as a human being of the nature of oppression that kills people and their culture — babies, women, old men and all. It is the same oppression that keeps third world people in the ghettos of the cities. . . My crime was not a violent act. It had no victims, other than myself perhaps. My crime was confronting a brutal system that denied me and others around the world the right of self-determination. . .

“This is the 10th year of our participation in the war in Southeast Asia, and it has been clear for some time to many that it was wrong. This being an election year, many politicians will at least say it was wrong. Yet I suspect that many of us will still be in jail this Christmas. . . Set us free.”

After his January 3, 1964 registration for the draft, Pat received a student deferment when he enrolled at College of San Mateo. He had just graduated from Balboa High School and had become eligible for the draft. Once he was no longer enrolled at SF State in the Fall of 1969, he immediately became eligible for the draft. The colleges were required to provide lists of enrolled male students which was compared to eligible draft registrations to determine who qualified for student deferment.

Since he was no longer enrolled, he was sent a draft notice to report for induction. During the trial, Pat expressed his opposition to the war, killing and martial living, though he did not request to be classified as a conscientious objector. He stressed the even more compelling factor of family hardship that existed, i.e., Alvin’s death in 1967, Canuto’s age and ill health, and the dependency of his four younger siblings as well as his stepfather upon him for support.

Within the context of Pat’s refusal to go to Vietnam and subsequent incarceration, he certainly did see himself a political prisoner for his views on racial inequality and ethnic oppression, and he sacrificed himself in keeping with his beliefs. He was very committed to his family, but also deeply committed to his ideals for all oppressed Third World people.

Pat was most certainly persecuted for his beliefs and not just his refusal to report. For the purposes of the Rolling Stone article, evading the draft was considered political, but so was the due process Pat experienced because of his social background. Within the context of Pat’s clemency report, his mother was identified as suffering from “serious emotional problems” and his stepfather as being “somewhat indigent, suffering various ailments, and semi-employed.” Being an ethnic minority, an immigrant, poor and a community activist were all ingredients for Pat’s persecution just like all Third World people during this time.

After Pat’s release from prison on October 16, 1972, the FBI continued to investigate Pat and his activities, even believing that he was a member of the National Committee for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in the Philippines (NCRCLP). The NCRCLP was established shortly after the declaration of martial law in the Philippines by President Ferdinand Marcos on September 22, 1972. Members were radical pro-Maoist Philippine and Chinese youths in the San Francisco area and the NCRCLP were associated with the I Wor Kuen and with Kalayaan.

I Wor Kuen, a radical Marxist Asian American collective, was organized in the fall of 1969 and maintained a national headquarters in New York. The I Wor Kuen’s San Francisco headquarters were at 850 Kearny Street, next to the I-Hotel. Kalayaan was an anti-imperialist organization and newspaper collective founded in June 1971 by Filipino American activists and recent arrivals from the Philippines. Kalayaan opposed racism and imperialism along with community support for the Philippine “national democratic” revolutionary movement. Due to Pat’s conditions for parole, his activities were severely limited to only attending meetings.

As a result of Pat going to prison, the Salaver family unit disintegrated, lost their home (which had been the center of PACE activity during the strike) to the bank which had foreclosed on it, and family members were separated and spread out throughout the Bay Area. The family’s financial, religious, and cultural efforts would be harmed significantly over several years as it worked to recover from this period. It was as if the long arm of the law needed to not only punish Pat but the whole family for its support of his activism against the establishment and the authority. Despite Estrella’s own political activism, she was not marching in the streets or leading students in tactics, but she certainly was lending her influence, guiding the students strategically and providing financial connections. (Gonzales, 2020)

For Pat to be in his role at SF State, it took a village of student, faculty, staff, church, community and family supporters and none were more supportive than the other PACE coordinators who worked with Pat to give the SF Filipino community what it needed with education and knowledge. Their efforts were purposeful for one of the smallest ethnic groups without an identity and that had been lumped in with all the “orientals” despite the Filipinos close history with the US. Pat said that Filipinos “just accepted that it wasn’t our society. You surrendered to the fact that you couldn’t be someone of authority. You didn’t expect to be a policeman, a doctor, or a politician. The jobs our parents had were as cooks or clerks or in the post office if you were lucky. Our people were farmworkers or in the laundries or in the service industries.”